by Mayumi-H | Feb 27, 2016 | From Hell (A Love Story), Publishing

Writing this post has made me feel like a bad writer-friend, even though there should be no reason for it to do so. Everyone’s opinion is their own, and part of what makes living in a so-called first-world country so great is that I’m allowed to have that opinion: no one is forcing an agenda or way of thinking upon me. Yet, when it comes to books, I feel ashamed to admit: I prefer paperbacks. I like hardcovers, too, though more for uniformity if it’s part of a series, or a version of the book that I really want to keep in good condition. E-books, though? I just can’t do it.

Part of my trouble with e-books is that, whenever I sit down in front of my computer, laptop, or tablet, I don’t want to read a book. If I’m in front of any kind of input-enabled device, I feel I should be writing. I’ve got enough stories I need to be working on, after all. Reading for pleasure is a hobby of relaxation and subconscious learning, for me. I like to curl up on the sofa with a blanket around me and a cup of hot drink steaming between the open pages of a book as my eyes and brain travel down the paragraphs, soaking up the story. I don’t get the same comfy, relaxed feeling reading from a screen that I do from a collection of bonded pages in my hands. Plus, a computer offers too many distractions, mostly in the form of the Internet. Yes, I know I can turn that part off, but it’s so ingrained in me to be online if I have the option to be online, and, pretty soon, I’m more involved with the technology of my reading device than I am in the book itself.

A friend swears by her Kindle. She is a quick, avid reader, and she enjoys being able to take a dozen books on a trip to the beach with her, all in a device less than the weight of a standard paperback. That is admittedly impressive. And, there is a lot to be said for the saving of paper by not printing a book.

Printing, for those of you who don’t realize it, is expensive by its very consumable nature. When I printed From Hell (A Love Story), each copy cost about $14 to make, full-color cover, 300-some-odd pages, the whole nine yards of processing and publishing. On the other hand, making the e-pub version – using Scrivener – took just a few keystrokes, some online storage space (which I already had), and the time it took to upload. In no uncertain terms: way less than $14. So, I can understand how e-publishing appeals from a business perspective, as well.

Many of my author friends (the real ones, with real books, of whom I do not consider myself a part, let’s be perfectly clear) have produced e-books or e-pub versions of their books. And, I buy them. Because these are my friends, and I want to support them. But, I have to be completely, brutally honest: it takes me at least a dozen times longer to read an e-book than it does a paperback. Some e-books, I haven’t even gotten to. They’ve been sitting in my queue for months, and I feel horrible about it. But when I open them up, and the words appear on the screen, I just. Can’t. Do it. I can’t bring myself to read a book on a screen, no matter how glowy the Kobo, how booky the Nook, or how fiery the Kindle.

I’m not sorry to you, Amazon, because you already get enough of my money. But I’m sorry to my writer friends. I’m sorry to the e-pub-embracing generation of writers and readers out there. And, I’m sorry, trees. But I love my paperbacks, so I’m not really that sorry.

Well, maybe for the trees.

What are your feelings about e-books? Do you have a preference for hard copies or e-pubs? Do you think I’m a bad person?

by Mayumi-H | Jan 16, 2016 | From Hell (A Love Story), Persona 4 Fan Fiction, Process

Since the first flash of a projectile from a barrel around 1000 CE, the gun has had a rich and varied history across most all avenues of life: social, economical, political, and creative. It also has the power to divide people and opinions like no other tool before or since. Let’s be clear: a gun is a tool. It is specifically designed to make easier the task of killing, of human or other animal. Now, one can certainly use a gun to accomplish goals besides killing – say, destruction of a barn wall, for those not well-versed in the skill of shooting a target – but their primary function is to kill, with more power, speed, and accuracy than any other weapon (assuming said gun is in the hands of an expert).

Politics aside, I have always found guns fascinating, especially their varied designs, and how beautiful they can be. Take a look at the craftsmanship in the Colt below:

I didn’t grow up around guns, but I had my share of toys for games of ranchers and rustlers with the boys next door, and I talked about them a lot with my father, who’d been an Army sergeant in Vietnam and who’d had an intense respect for firearms and war weaponry in general throughout history. He’d impressed upon me at a young age that guns are dangerous, doubly so if they’re not handled with respect. As I got older, we delved into the specifics of them: “I would much rather you know how to properly use a gun and never have to,” he’d say to me time and again, “than find yourself in a situation where you had to use one but didn’t know how.” He never squelched my interest in them, but he always made sure I understood the inherent danger in them, and the enormous responsibility a person has whenever they pick one up.

I’d written stories with characters who’d used guns since I was a kid: Han Solo’s DL-44 heavy blaster pistol, the Enterprise crew’s type 2 phasers, my D&D-inspired thief’s flintlock pistol. In those early forays, guns were simply weapons of convenience that often made a cool noise or shot a bright laser beam, and I didn’t think much about their impact (pun not intended). It wasn’t until a few years ago, when I wrote the gunsmith in From Hell (A Love Story), that I really thought about what I was saying about guns through my stories when my characters squeezed a trigger. There’s a semi-pivotal moment in the story where this gunsmith and the main character argue about throwing blind cover fire into a crowd of civilians. The gunsmith’s argument is that they’re surrounded by people, while the main character points out, “Yeah, and at least one of them is shooting at us.” The ramifications of their choices follow them through the rest of the book, but it was important to me that both of them realize: odds are good that when you pull out your gun, people will die.

Because I’d grown up being taught to respect – not fear – guns, I wanted that respect to come through in this story. Even in the books and stories I was reading to get a feel for a dirtier galaxy based on the Old West, the characters treated their guns like the closest partners they’d ever have, which was probably pretty close to the case in those wilder frontier times.

Stories are not soapboxes, though, and it can be difficult for a writer to separate their personal views from those presented within their prose. Firefights offer great opportunity for excitement, high action, and conflict. But a quick-trigger topic like gun use (ha ha) requires at least some responsibility on the writer’s part. Like any weapon, they’re dangerous, and our stories would lose a measure of realism without addressing just how dangerous they can be. We can do this through the actions, reactions, thoughts, and dialogue of our characters, as well as offering realistic depictions of what happens when those characters use their firearms without awareness, caution, or respect.

Have you ever written a gunslinger? What do you think about guns – or any weapons – in stories? While realism is important, how much do you think a story requires to be seen as effective in its telling?

by Mayumi-H | Sep 25, 2015 | Fearless, Finding Mister Wright, From Hell (A Love Story), Process

September seems to be a popular birthday month. It must have something to do with cuddling together when it’s cold outside during the traditional winter. I celebrated my birthday this past week, too. While I may not have been able to celebrate with everyone I would have wanted there, I did enjoy a very fun and filling tasting menu supper in the city.

But I’m not here to talk about indulgent food.

Recently, several storyteller friends of mine have brought up the topic of scenes or chapters in a story where nothing really happens. There’s no big action, no deep conflict, just the characters slowing down to talk, reflect, or enjoy themselves. The prevalent argument in today’s how-to columns is that every scene should push the story forward. In some cases, that technique works: strict short stories, for example, where the prose should be so airtight that every dialogue and action needs to contribute to the plot. For a longer story, though, I believe slow-downs are necessary.

A story can’t stay at 11 all of the time. The characters – and the reader – need some breathing room between the big conflicts. This downtime can be represented in any number of ways: a conversation, a love scene, even a birthday party.

For some reason, I like using birthday celebrations to look at a character’s life. In 1 More Chance!, I used Chie’s boyfriend’s birthday to introduce her to his family (among other things). In Fearless, Ross’s birthday is an excuse for his crew to get together for a party on the beach. In the “Finding Mister Wright” universe, Rob’s birthday is used to contrast the ideas of life and death. And, in my most recent story on the subject, one of my From Hell bounty hunters uses an old birthday to bury his past. Now, 1 More Chance! is a massive, meandering relationship story, and the “Finding Mister Wright” and From Hell examples are self-indulgent free-writes, so they follow their own non-rules. The Fearless birthday chapter, though, offers what I’ve always thought to be a necessary moment of relaxation between the second and third arcs, where the characters get to have a little bit of simple happiness before the new conflict hits. Seen alone, the party on the beach doesn’t do much for the novel as a whole. The main point of the chapter is to show how well these characters fit together, and how far they’ve come from the beginning of the story. There’s not much more to it than that. But I think it’s good to have smaller, calmer moments like this in a story, to show the reader who and what has been affected by the conflict that’s happened, or by the conflict yet to come. And, just as it’s good to have these smaller, calmer moments in stories, it’s good to have them in life.

Birthdays are as much about our own growth as they are about family, friends, noisemakers, and food. That growth includes rest as well as action. So let’s push on with our stories. But let’s also not forget to allow for a little bit of breathing room now and again.

What are your thoughts on quiet moments in stories? Do you ever use a birthday occasion in your stories? What kind of birthday cake do you like best? 🙂

by Mayumi-H | Sep 2, 2015 | From Hell (A Love Story), Publishing

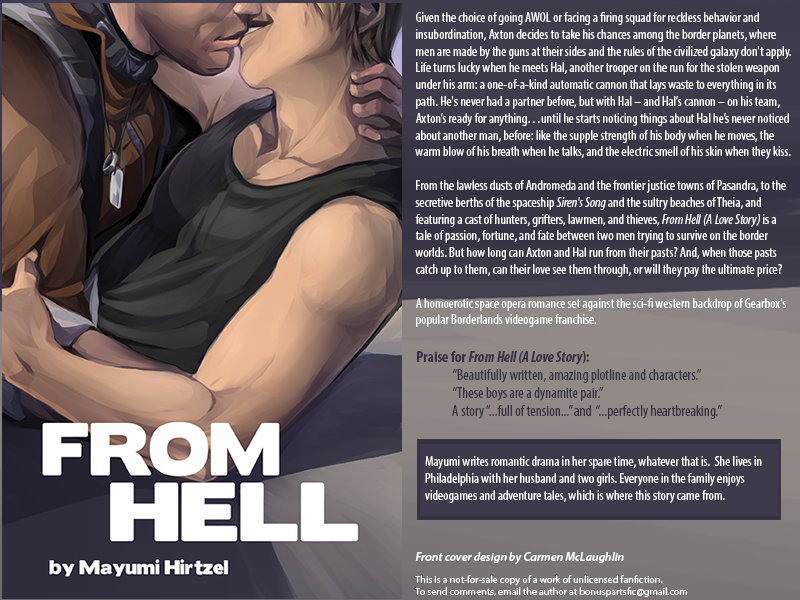

Clicking the cover image will take you to the PDF e-book version. You can also read the chaptered versions on Fanfiction.Net or AO3.

If you would like a free paperback copy, contact me.

by Mayumi-H | Jul 18, 2015 | Fearless, Finding Mister Wright, From Hell (A Love Story), Process

Writing has a lot to do with first choices. We write from the tips of our fingers, trying to get down all the words running in our heads. When we sit back and take a read through what’s on the paper or screen, we can start to second-guess those words. I’ve written enough first drafts – enough words – to know it’s okay to trust my first choices. They’re usually right. But, sometimes, they’re not.

After I’ve finished a story, I’ll let it sit a while. For a short story, maybe a few days; for a novel, sometimes as long as a year or more. When I go back and read it again, it’s easier to see which first choices were right and which ones were, well, not so right as I’d originally thought. That distance is important. It grants us a fresh eye and fresh mind. It also grants us greater honesty with our work. Hopefully, we’ve grown from that first draft, using other stories. The distance, honesty, and experience work together to help us see that draft in a new light. If we’re ready, and inclined, it puts us in a better place to cut, weave, and create a more perfect story than what used to be there.

All of this is just me saying that I’m back in editing mode again. I’ve pulled up Fearless and have started to go through it piece by piece, chapter by chapter, conflict by conflict, to make it a better story than it was, even if it’s never perfect. I loved the story then and I love it still. I’ll likely be doing some more off-the-cuff writing while I edit this time, though, because I learned from the From Hell edit that I get a little lost when I’m not creating anything new. But I’m ready for this next challenge. Let’s see how good my choices were the first time around.

To celebrate this new chapter in my own journey, I pounded out another short-ish free-write set in my “Finding Mister Wright” universe, where the Wrights and McAllisters talk about, fret over, and celebrate their own first (and second) choices.

“First Choices” (~2700 words/9 pages; PDF will open in a new window)

Have you made any first choices lately with your writing?

by Mayumi-H | Jun 27, 2015 | From Hell (A Love Story), Process

I just got back from a work conference on television technology and production (that’s my day job). I had a great time, as I always do, connecting and reconnecting with colleagues from across the country, and learning new lessons from faculty, staff, and students working in video. I also attended a great session on reality TV production, presented by April Lundy. I’m not a big watcher of reality television – the closest I get to it are cooking shows or travel docs – but I was riveted by Ms Lundy’s session. Because so many of the points she made were about the importance of storytelling.

“Storytelling is everything,” she told her attentive crowd, and I grinned as she said it, because it’s true. Whether in television, film, poetry, or prose, the story determines the success of the medium. Ms Lundy spoke a lot about the ups and downs of conflict and arcs within a successful reality television show season or series. I could only think how much that applies to my own writing and editing; throughout the entire editing process of From Hell (A Love Story), I kept reminding myself to “keep to the arc” and “push toward the conflict,” and how each chapter – just like a television episode – needed to fulfill a thematic point in the ongoing story. When I spoke to her after the session, she said, “I kept looking at you, because I could tell you understood [how important story is].” Do I ever.

I wasn’t able to write much more than a fluff piece for my wicked gunslingers while I was away, but I thought about my writing craft a lot. And I’m already itching to get back into it, conflict, plot building, character nuances, and all.

I love it when my work and my passions converge. Have you ever had two parts of your life cross paths in an unexpected way?

Recent Comments