by Mayumi-H | Jan 30, 2013 | Process

Many artists – sculptors, poets, fantasists of all kinds – attribute inspiration for their work to what they call their Muse.

“Hesiod and the Muse” – public domain image

Not to be cruel. Because, as artists, we’re all rather flighty individuals, with our minds dwelling at least a little bit in the clouds. That’s okay. Without dreamers, society would be pretty boring. Actually, it likely would have died away by now, without any high thinkers, who wrote some of the most important words of our civilization, from “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” to “We hold these truths to be self-evident….”

But ascribing your talent to some sort of divine guidance is – oh, I’m just going to say it. It’s kooky. More than that, though (and I’m going to catch a lot of flak for this, I know), it’s lazy.

Now, before my ever-dwindling group of blogging and writing friends decides to pull out the lynch ropes, let me clarify.

I’m not talking about artists who decide they need to step back from their art and re-prioritize; those folks know they’re just putting a muzzle on their Muse for a bit. Nor am I talking about the artists who simply know themselves well enough to decide they’ll make their art when it suits them, all in good time.

I’m referring to the people out there who complain they have no inspiration to create…while they can still pick up a videogame controller for hours on end, or head out to the pub the whole weekend long. That has nothing to do with the attention of your Muse.

Now, I completely understand the charm of having some seraphic creature looking over your shoulder, telling you which way to move your pen. And I, myself, believe that – in the throes of a story – a character or characters can take over, using their voices to weave new and intricate tales I’d never even considered while I was in the plotting phase.

But, don’t be misled by the flowery notion of a Muse. Those character voices are your voices. Any new paths toward which they may pull you are functions of your own creative subconscious. It’s a wonderful experience, to guide a story in an unexpected direction, based on the whim of a single word or phrase. But you have created that word, those phrases, that heretofore unknown story arc that turns your hunter into the hero, or your princess into the warrior demon. It didn’t come from any outside force.

What are you waiting for?

It’s not the idea of the Muse with which I take issue. I take issue with the idea of waiting on a Muse to move your pen (or hammer, brush, bow, or lens). That takes the power of creation away from the artist. Even worse, it takes away the responsibility for that creation. When an artist whines, “I’m waiting for my Muse,” that’s just an excuse for being lazy.

You cannot wait for some capricious, aetherial harlot to come knocking on your door, tapping at your shoulder, whispering into your ear that now is the time for you to make real all your hopes and dreams. No outside force is going to make your art for you. You are the only one capable of that. You. Or, I. Nobody else.

Blaming a Muse for lack of inspiration or failure to produce the story, the music, the picture you want is a cop-out. When you call – when you make the choice to apply yourself to your art, whatever it may be – your Muse will come. And, if she doesn’t, you go get her. You grab her by her flowing toga, and you drag her over to your workstation. Because you can’t afford to wait for her.

Because you are your own Muse.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3C3poU_0sK4]

Now, for those of you still with me after that little tirade, tell me: How do you motivate yourself?

by Mayumi-H | Jan 19, 2013 | Fearless, Short Stories

It’s a threesome this week (no, not that kind of threesome, silly!), as I attempt to combine prompts from Julia’s 100-Word Challenge for Grown-Ups, Lillie McFerrin’s Five Sentence Fiction, and The Daily Post Writing Challenge!

Julia’s prompt this week (week 73) is “…the notes from the piano…“ Since we are to incorporate said phrase, we’re allowed to go to 105 words instead of the standard 100.

Lillie’s prompt this week is FORGOTTEN, and we’re to construct a story around that theme, in five sentences. We don’t have to use the prompt word itself.

The Daily Post’s prompt this week is Starting Over. There are no constraints on word or sentence count.

Let’s recap: 105 words, five sentences, with themes FORGOTTEN and Starting Over, and including the phrase “…the notes from the piano….”

This is my first time trying to pull together three different prompts around one idea, but I think I did pretty all right….

“Stagger to Sway”

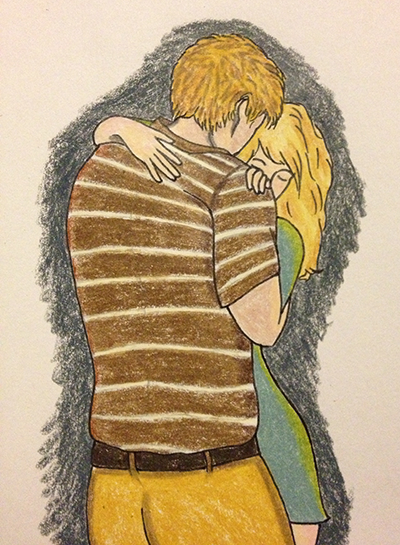

Dance, he’d said, as if she could do; her dumb legs could barely remember how to stand, but for the clanking metal of her Zimmer frame! He’d never let her sit back, though: from grabbing her first wave, to making her step up from her chair.

“Everyone’s staring,” she protested.

Tugging her up, he muttered, “Forget ’em,” and, using his hips and shoulders, he took the place of her Zimmer and helped her lurch, inch by staggering inch, from sofa to open floor.

She cursed such slowness…but, in his arms, as the notes from the piano reached her, they began to sway, and she forgot.

(Yes, I know, I forgot pockets. Just as in real life, though, I got distracted by the bum.)

This vignette derives from an early (scrapped) draft of a scene from Fearless, so the characters and conflict are likely familiar to my beta readers. However, the original scene read as too schmaltzy for that particular part of the story (and, you may think it does so, here, as well), but I’d still rather liked it, at its core.

People say you should never completely scrap what you write, because you never know when it may come in handy. I had to do a fair amount of tweaking, but this stands as one of those lucky moments when I got to go back to something I wished I’d been able to keep in the story proper.

Did you play with any of these prompts this week? What happened with the notes of the piano? What was FORGOTTEN? How did your characters Start Over? Let me know!

by Mayumi-H | Jan 5, 2013 | Process

“F***,” Ross swore to himself as soon as he’d closed the door to the loo. Another quietly hissed, “F***,” as he wrenched the metal faucet handle open, and a third as he clenched his fingers beneath the flow of water.

Shouldn’t have come what are you doing here you don’t belong Sam‘s right–

And, of a sudden looking up into the mirror above the sink, he saw the reflection of that oddly proper but still charming wave walker, with the blond hair and clear blue eyes, in the dark shirt and silk tie, and stopped.

“No,” he told that man in a whisper. “It’s just one night. You can do this.” He splashed some water on his face, to cool the flush of red behind his eyes, and looked into the mirror again with a determined stare. “Just keep your bloody mouth shut.”

Apologies for the coarse language above, but I wanted to illustrate a technique used quite a bit in fiction: the inner monologue. Or, put more basically, thoughts in a character’s head.

I try not to dwell in a character’s head overmuch. There are times when it’s convenient to make a point, but I’m well aware that the inner monologue can be a crutch, where the danger is I’ll be informing the reader (telling) of a character’s motivations or feelings rather than letting the character’s actions make those motivations and feelings known more organically (showing).

Almost worse than this fallback to telling, though, is when I see some writers use the inner thought convention in a way that is so formal it becomes unnatural, cumbersome, even. Thoughts become like words spoken aloud, as you might see in a comic book thought bubble…

…when I don’t know of anyone who thinks in structured sentences.

Now, I don’t take issue with a simple thought such as “War sucks,” which is basic and visceral: the emotion is broken down pretty much to its core as can be done. What I do roll my eyes at is a chunk of text broken out as a character’s inner thoughts that is structured so much like a proper paragraph that it could just as well be spoken. That it probably should be spoken:

Perhaps I should go to her, standing there in front of her locker, and ask her if she’d like to go to the dance with me. Just go up and ask her. How hard could that be? If she says yes, maybe I could bring her flowers, too, to show her how much I like her. But what kind should I get? She’s said peonies are her favorite, but what if the florist doesn’t have any peonies? What are peonies, anyway? Oh, blast! Why does young love have to be so complicated?

This is overdoing it, of course, but you get the idea. How boring is that, to be told outright – through an inner monologue, no less! – what the character is thinking and feeling? How much more interesting would it be to guess a little:

He shifted on his feet as he watched her giggle among her friends. Even the way she opened the locker door was full of grace, fingers clutching her books like they were delicate flowers.

Didn’t she like flowers? He’d heard her talk once about peonies – whatever they were – in some conversation or other. Maybe, if he came to her with those before he asked her to the dance, she might notice him, for once….

Actually, I’m not sure if that’s better or worse. 😉 I do know it’s more interesting to write, though, so hopefully it’s more interesting to read.

The inner monologue is a perfectly acceptable convention. Just remember that it shouldn’t be your answer to all explanations. Thoughts are in our heads for a reason. Words from our lips just the same.

Do you employ the inner monologue? If so, how? And, which of those examples do you prefer, if either?

by Mayumi-H | Oct 20, 2012 | Process, Uncategorized

Part of what makes stories so much fun is the drama involved: Will the hero conquer the villain? Will the princess find her true love? Will the puppy make its way home? But, what happens when we find our characters strive more for realism than for drama?

Every story needs some kind of emotional resonance for it to have impact, whether it’s about war or heartbreak or family experience. Sometimes, though, our characters become so much their own people that they end up dictating where their own stories go. I’ve written scenes – necessary ones – for their dramatic effect…but I’ve also had to rewrite other scenes because the characters’ voices had developed so much since my initial plotting that their actions (or reactions) as I’d originally envisioned simply no longer held true to their natures.

What do you do in this situation? Do you let the character take over, possibly sacrificing the drama of the scene? Or, do you follow through with the original idea, possibly sacrificing believability for the character?

It’s okay to play Loosey Goosey in some instances: maybe the hero isn’t in his right mind at the moment and makes a snap judgment against character; maybe the heroine is torn by the conflict facing her and decides on one route over another because her values are confused. Written well, with the associating consequences, those options are totally valid. But, what do you do when your original big conflict becomes significantly less climactic than originally envisioned, because your darned MC has grown up too much over the course of the story?

I’m a big fan of sweeping epics, and last-minute, nerve-wracking climaxes where the audience is led to page after page to see what happens next. But I also believe in, well, believability in a story. The hero shouldn’t overcome the conflict just because the story needs a climax; he should do so because that’s what he has to do, to progress, grow, and change. It may make for less high drama, but it may also make for more realism.

But that’s just my opinion. Which do you prefer: realism or drama?

by Mayumi-H | Sep 8, 2012 | Process

Many of us have already been told it’s better to keep our prose as simple as possible: clear is better than clever, as they say. For the most part, I agree. And I’ve enjoyed my share of flowery prose! One part of a story that’s created something of a dividing line between me and other authors, though, is just that: the dividing line. To put it more broadly, the use of transitions.

Keeping in mind that adage of clearer being better than clever, I don’t see much point in dwelling on long, rambling transition sequences. But, I also think the dividing line is a bit of a cheat. Not only does that divider line (or space block, or asterisks, or whatever) take the reader out of the moment, it breaks the flow of the narrative. Sometimes, this doesn’t matter so much; if you’re changing perspective, for example, you want to separate the narrative flow somehow. But for a subtle scene or time change, I prefer to keep reading, rather than having my eye stutter over a visual division.

The rest of the afternoon passed quickly: the relatively uneventful walk back to the city centre, with St. Stephens and the train station, and a bit of aimless traipsing around the shops while the hotel prepared their late check-in room. Sally led them into a book shop where they stopped to listen to a charming children’s reading circle; Larry dallied in a retro art store with a selection of colorful and odd-looking international movie posters.

The quaintness was charming, of course, and they chatted along the way about both realistic potentialities and dreamy might-bes. But, through it all, there was still something missing, something hovering almost expectantly in the air between them: when they’d stop at a corner, or pause in conversation, or share a quiet look over tea and biscuits in a coffee shop.

Now, the above doesn’t really move the plot along any; all it does is take the reader from one scene to another. An editor might tell me to cut it. Simply removing these paragraphs between the two scenes makes my brain stutter, though, the same as putting in one of those divider lines would do. So, I’ve indulged myself with this transition.

What are your feelings on transitions in prose?

Recent Comments