by Mayumi-H | Mar 27, 2013 | Process

Most folks likely didn’t notice, but I was away last week, “away” meaning cramped into an editing suite, poring over timecode and doing frame extraction. I’m back again, but last week’s work has stayed with me. Mostly, because editing video always makes me think of this scene: the Warriors gang fighting off the Baseball Furies, from the 1979 film, The Warriors.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zL0ipXUD-uU?rel=0]

Oh, Ajax, you pithy pugilist, you!

A fight scene without a soundtrack instantly feels much more violent than a fight scene set to music of any kind. That silence can often work in a filmmaker’s favor. Director Walter Hill says he wanted to preserve a cartooniness with this scene from The Warriors, so he kept the music in. That’s not a critique, for musical sound and rhythm can also do a fine job of adding tension, excitement, and drama, just as well as silence. It all depends on how it’s used.

When we write, we’re not given the luxury of pumping music at our readers. So, how do we create the same level of tension with words alone?

One idea? Choose your words carefully for more than just their meaning.

Writers often think they work in silence, because words are static on a page. But the rhythm of words can be just as important as what they mean. Poets and lyricists understand this better than most other writers, because their space, time, or meter is often limited. But even the self-proclaimed short story writer or novelist shouldn’t ignore that poetic ear.

Try speaking your scene aloud. You’ll hear how the choice and cadence of each word interacts with the ones to follow, and how those interactions affect the way your story is told.

Have you ever read a story that was just he said after she said, all the way down the page? There’s nothing wrong with that approach – it’s certainly serviceable to a story. But, words can move people by more than just their definitions. Why not let them do that?

Now, lots of writers and editors will tell you that prose and poetry are two different styles for a reason. That’s not incorrect. And, it may not be the best idea to turn your action thriller into a garden of flowery prose. That’s not what I’m saying, though. I’m saying, words should fit the moment, theme, and emotion of the story being told. Even readers advanced enough not to have to read aloud will still hear those words in their heads.

Study a good action scene. The words and ideas come quick, like lightning, one after the other. No time to describe in minute detail. Why? Because it slows the reader down. On the opposite hand, study a moving scene of gentle emotion. Words move more slowly, here, like leaves drifting on the wind, spiralling to a quiet settling on the ground. An argument will crackle, snap, and finally flare up like a paper bag thrown on a fire; a sex scene will start small and grow, mounting higher and higher until it crashes like a wave against a beach, where it eases down to foam again.

Brian Robert Marshall [CC-BY-SA-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Do you have any such rhythm techniques when you write? Which are your favorite types of scenes to write? Why?

by Mayumi-H | Mar 13, 2013 | Process

I hadn’t meant to kill her.

I certainly didn’t start out the day planning for it to happen. I didn’t even know it was happening, until I looked at what I’d wrought, and realized she was dead.

Somewhere deep down, though, I knew: it had to happen. I’d been waiting for it to happen.

That knowledge didn’t make it any easier to do. It didn’t make the squeeze of the trigger any less jerky, or the thunder of the shot any less loud. Or the pain I felt watching the once-bright light in her eyes go out any less acute.

One moment, she was there: fighting, struggling, strong. And the next, she simply…wasn’t. She wasn’t there. She wasn’t anything. She was just gone, like she’d never existed in the first.

I cried when I killed her. I honestly and truly did.

Sitting back, I had to stop. Everything. And let her have that one moment of my reflection. Because I hadn’t given her the chance to have anything else. Not the happiness she’d sought, or the love she’d desired. Not even the fleeting freedom for which she’d run and fought so hard.

I’d never killed anyone before. Not anyone who’d mattered. Flitting bystanders with no histories, random casualties of war: they didn’t make a difference. They had no stories.

This one, though. She’d had a story. A story I’d cut short, for a split-second of excitement. For the sake of mere plot.

“Acceptable losses,” I called her, the next day, after I’d had the time to reflect. A phrase to describe her and her ilk, the ones I’d left soulless and smoking along the way. Because in love and war, sacrifices must be made.

I knew it was for the best. I knew it had to be done.

But, I’d still cried.

I’ve been thinking about this topic ever since a recent blog post about what heroes can do, by Vanessa-Jane Chapman.

I’ve always thought death in stories should be warranted. Many of them are. They’re often valuable for completion of a story. But, when it came time to do the deed, myself, with one of my own…it got to me.

Let your story go where it needs to go, even if it’s someplace terrible. You may end up stronger for it. Or, you may end up realizing you’re not as nice a person as you’d always thought you were.

Death in your stories: how do you react?

by Mayumi-H | Mar 6, 2013 | Process

Writers’ Museum in Edinburgh. In Lady Stair’s House. Photo by Jeremy Keith.

Now, I’ve shared my stories with others before: friends, writing buddies, family (once in a while), even strangers. I don’t stress about feedback from any of those folks. They receive my stories as a chunk of text to absorb, and, for the most part, their feedback is a simple, “I liked it,” or “I didn’t.” We may go into slightly more detail than that, but it’s often conversational, with comments painted in pretty broad strokes.

A professional edit, though, picks a story apart scene by scene, line by line, word by word. That’s good. It helps a writer step outside the confines of their little self-imposed world, to have someone examine that world with a sharp, precise knife and cut where necessary. They may do a little triage, too, to keep the story pumping. I’d trust an editor – especially a good one, like I was lucky enough to get – to do that.

When I received the pages back and finished reading through all the comments, I wanted to scuttle back into my NaNo hole and tear the whole story apart again. Not because I was crushed or demoralized by those red marks. Because those red marks showed me there was something there. And I wanted to fight for it. I wanted to dig deeper into myself and that world and those characters, and make the story better. Because, with those fixes and suggestions, I knew it could be so.

I didn’t think I’d pick up that story again. It was a first draft, and first drafts always need work. But, when I crossed the NaNo finish line last year, I thought, Good enough. Now, I know how wrong I was. The best bit? The editor never came out and told me I could do better. It was everything between the lines: all the little ticks and tacks that – when I saw them – I knew were right.

In hindsight, I shouldn’t have worried. The editor’s feedback was great. Not to say it was all glowing praise, because it wasn’t that. Rather, it was observant, critical, and helpful, what a proper edit should be. And, just reading through the comments for that one scene made me realize the story wasn’t all it could be.

I wasn’t all I could be.

So, I decided to take the pages back and start over. Not from scratch, because I do like a lot of the story already. But the suggestions and observations are with me every time I start to play in that world again. And when I play in all my other worlds, too.

The story may never be great, or a bestseller, or even publishable. But I can make it better than it was before.

Better. Stronger. Faster. Dah-na-na-naa! Dah-na-na-na-na Na-na-na-naa!

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HofoK_QQxGc?rel=0]

What words of wisdom do you have for a hopeful aspirant? Got stories of your own to share? Want to trade? Let me know!

by Mayumi-H | Feb 27, 2013 | Process, Uncategorized

One of the great aspects of sharing our work on the Internet is the tremendous community of people available to see it. Many of these folks can provide valuable feedback, insight, and advice, and they do it for free.

But, just because something comes free doesn’t always make it good. Good critique comes with a price. Often, it’s a monetary price. Make no mistake: that monetary price is worth it, if you’re genuinely interested in getting sharp, honest critique of your work, especially with an eye toward eventual publishing. Not all of us are looking for that, though. Some of us just want to get some more in-depth feedback than, “This is great!” or, “Post more soon!”

For those of you just getting into the tricky business of giving free feedback, here are a few (hopefully helpful) tips.

El editor enmascarado! (public domain image)

- Check your ego at the door.

Whether critiquing someone else’s work or having your work critiqued by another, you must swallow your pride.

For the critic, ego-checking should be pretty easy to do. You’ve been asked to do a job, and your goal should be to complete it to the best of your ability. However, try to rein in any impulses to create a mini-You. Each artist has his own style and story, and trying to rewrite that to fit your own won’t help him become a better craftsman.

For the artist, ego-checking can be slightly more difficult, as our stories often feel like part of us. We’ve invested time, effort, sweat, and tears in them, and to hand them over to another person may induce fear and anxiety. But, whomever we trust with critique, we should listen with open ears to their feedback.

Read that last sentence again. Feedback. Listen. Trust. These are not given – or received – easily, which is why you should also remember point number 2…

- Critique unto others as you would like to be critiqued.

If the critique is genuine, there’s no reason to fear the red pen. Any artist who asks for your help will want you to point out what works and what doesn’t. Because learning where we make mistakes should make us more aware of them in the future, and help us hone our craft.

That being said, remember this is a person who has asked for your help. By nature, people are fragile things, artists often more times so.

When you strike with your red pen, do so honestly. But, be helpful, too. If it’s an error you’re marking, illustrate a corrected example. Issues with the plot, characterization, or pacing? Define them for the artist: let him know where you thought the story slowed down and how he might compensate for that. Tell her why you found the plot meandering and what she might consider changing to pick up the pace. If you don’t like a character but you’re supposed to do, tell the author what traits or scenes counteracted their intentions.

The Golden Rule applies to all interactions, though. Work your red pen as you’d want others to do to you. We all come from different walks of life, and we’ve all got different styles. Which brings me to point number 3…

- Assume nothing.

There’s an old saying that goes, When you assume, you make an “ass” out of “u” and “me”.

Avoid assuming anything before you go into a situation or story. Your artist probably comes from a different background from you, so her story will be different from any perceptions you may have at the outset. Which is why you should try to keep those perceptions under control.

Certain aspects of storytelling will hold true unilaterally, across the board: solid plot, good characterization, proper grammar and formatting. Beyond that, though, you need to let an artist find her own way.

Now, an author should do their own research into the subject about which they’re writing, at least to the point of it being reasonable. I wouldn’t expect someone to get a degree in astrophysics just to write a few lines of dialogue, after all. If something doesn’t seem right, mention it. But keep in mind the geographical, societal, even temporal boundaries of the author’s story. Coffee may be the most popular drink where you are, but if in the story it’s tea, then it’s tea. Live with it. If, on the other hand, the author mentions how Kansas is in South America, you need to correct that. An author looking for guidance will thank you for your attention…or, he’ll have an opportunity to explain his choice. Either way, you’re doing your job as a critic.

So far, I’ve been blessed to have readers who have been equally honest, straightforward, and supportive with their critique when I’ve asked for it. I hope you’ll be so blessed, too, either on the sharp end of the pen or not.

What are your tips for critiquing others’ work? Or, for having your own work ready for critique?

by Mayumi-H | Feb 20, 2013 | Fearless, Process, Short Stories, Songbirds

For the scrapheap

Sometimes, a challenge prompt will strike an immediate chord with me, and writing a submission is no trouble. (My Songbirds series vignette “A Deeper Reflection” was one of those easy-peasy efforts.) Other times, a multitude of prompts will converge into a perfect storm of inspiration and interpretation, such as with “Stagger to Sway,” one of my Fearless side stories. And then, there are the times when I’ll start writing one way, go another direction, twist around yet another bend, until I finally end up with a piece suitable for public consumption.

In the case of the “CHERISH” prompt, I eventually settled on a somewhat humorous entry, but below are three other efforts I deemed unworthy, for one reason or another. Take a gander, if it please you.

“Rescue”

That first shriek – echoing along the coastline like a banshee’s wail – made Scott drop his board like it was on fire; Finchy and Niall were already tearing across the sand, arms pumping for speed toward the source of those cries. Scott followed quick as he could do, only to pause at the edge of the scene: a young mum bouncing a screaming little girl close to her breast, while a frazzled dad was on hands and knees, scrabbling in the sand.

“Lost doll,” Niall said, his voice ripe with sour disappointment.

Scott almost snickered, when a glance into that girl’s reddened, snotty face made him think of his own tiny Emma, prompting him to shove both his mates toward the beach with a sharp, “Don’t just stand there. We’re a rescue squad; let’s rescue!”

* * *

“Toothless Shark”

Venus knew they had sex. As quiet as they’d tried to be, the rhythmic creak of used springs was as tattling as a two-year-old. So when she had to creep past their bed to the bathroom, she always kept her gaze trained forward, for the sake of all their dignities. Except for this time, when she glanced reflexively toward the sound of a muffled sniff, and had to cover her mouth and hold her breath against the most itching, adoring whimper, at the sight of Finchy’s face pressed into Amber’s ruffled curls and his fingers linked loosely with hers.

Swinging the bathroom door closed behind her, Venus laughed softly into her palm, wondering what the rest of the crew would think if they saw their resident shark, now.

* * *

“One”

At the precipice, she stood, white and bright and beautiful, the whistling wind swirling her golden curls around her shoulders the same as it ruffled the edge of her dress around her legs.

Seeing her so, warm sweat formed in his palms. He shifted his hands to his sides, to wipe them down, when it suddenly became too late: she grasped his fingers with her own – cool, slender, soft – and moved up close to him, for this moment that would end their lives as two.

They exchanged the words between them, and the precious circles the same. A single kiss, at last, and that was all, to soothe the anxious patter of his heart, and to make them one, for ever.

Now, I don’t think any of these are terrible. I was determined enough to want to finish them, after all (and to be willing to share them, here). But, as you can hopefully see, devoting such effort to these challenges is time-consuming. Even though I’ve decided to cut my blogging down to two posts a week instead of three, these still take plenty of concentration. I don’t like posting my work if I’m not totally pleased with it; I owe you that much.

…Focus…!

So, if you liked any of these scraps at least a little bit, remember this: even if what you write doesn’t make your final cut, keep that effort. Don’t throw it away completely. You never know when you might need that smile.

Where do you keep your scrapped efforts? Have you ever used a scrapped effort to start a new project?

by Mayumi-H | Feb 13, 2013 | Fearless, Persona 4 Fan Fiction, Process

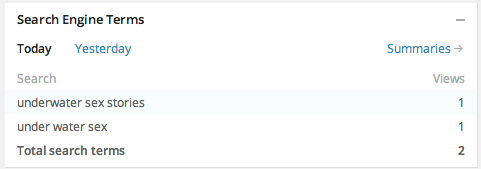

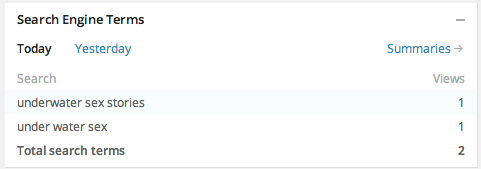

I was going to put up a post about how to give good (amateur) critique, but I decided to go a different direction, because I saw this come up in my hit statistics…again:

Am I really this predictable?

For those of you who are sensitive to the subject of sex, you may want to steer clear of this post and come back on Saturday, when I’ll post some original fiction. For those of you brave enough to continue, though, let’s get wet!

“So…did you?” Niall asked, and Ross blinked.

“Did I what?”

“Have a bang on the beach last night,” Niall said, and gave a distasteful waggle of his tongue.

Ross scowled. “Sex on a beach is tacky,” he said, which was true…not to mention, sand had a tendency to get everywhere, which also made it damn uncomfortable.

Every good romance has some naughtiness to it, whether it’s of the fade-to-black kind or the in-your-face variety. I’ve written both, and I’m of the opinion that each version has its merits…and demerits. No matter how you choose to write your raunch, though, there are a few practicalities to keep in mind:

1.) Sex on a beach is tacky.

It’s an orgasm metaphor.

Let me save you the trouble: having saltwater shoot up your nose while you’re snogging your lover is not a pleasant feeling, no matter how locked your lips are. We’re not even going to talk about how crashing water will make a swimsuit move all over the place, creating uncomfortable ripples and folds more likely to cause laughter than lust, or how sand does, in fact, have a tendency to get everywhere. Even a wetsuit won’t keep that pesky stuff off your skin. Which is why you should always rinse off before you hit the sheets for a post-surf romp, unless you want to be cleaning sand out of your bed for weeks.

A beach can be a romantic place for a tryst, to be certain. Just be certain to remember what else is on a beach, too.

2.) Water is not the same as lube.

“Come on in! The temperature’s fine!”

But, when it comes to sex, be aware of the surroundings, especially if it’s water. We’ve all heard the story that you can drown in even a puddle of water, but water can also counteract the benefits of personal lube. The human body produces its own lubricant, which is designed to smooth out the sometimes-rough mechanics of sex. Water, on the other hand, being the excellent cleaner it is, has a tendency to wash away that lubricant.

Yikes.

So, next time you think about putting that steamy sex scene in a steamy shower, keep in mind the details of such a situation. And that’s not even mentioning the aforementioned issue of rushing water in the face and up the nose….

3.) You’d never mistake a pool for a condom.

A swimming pool offers all the joy and excitement of a midnight skinny-dip without the associated danger of salt poisoning and night feeders.

The dating scene is full of sharks of all kinds….

Which brings me to my last point:

4.) Lovemaking can be lovely, any place.

Don’t let me discourage you, or your characters. On the beach, underwater, in a pool, even in the rain: sex between two people brought together by love can be beautiful, in any location and under any circumstance, so long as you make it so. Even in the typical locale of a shared bed, sex can be thrilling, romantic, ecstatic, funny, relaxing, fulfilling…all this and more. It’s truly about what your characters – and your readers – feel from that love that’s important.

Just remember to think before you put them in a wet situation. 😉

Have you ever written a watery sex scene? Would you ever write one? Why, or why not?

Recent Comments